Need for Public Education & Policy

Building Support for Solutions

Environmental and economic injustice are prevalent across Appalachia. Communities of color and low-income communities are disproportionately exposed to and burdened by the hazards associated with coal mining. While recent years have shown a decline in coal mining, mountaintop removal is still happening, abandoned mines are still polluting, residents have a higher mortality rate, and taxpayers are still carrying the burden of an industry that has dodged responsibility and accountability for the devastation left in its wake. Relying on a mono-economy of fossil fuel extraction has accelerated climate change, and led to increased poverty and unemployment.

Members of The Alliance for Appalachia conducted a grassroots listening project around the issues surrounding the collapsing coal industry, and the overwhelming point of unity was the need for an extensive public education effort to better inform community members and other stakeholders of the looming post-law mine abandonment crisis, and to build support for policy proposals to address the situation. Our intent with this webpage is to define the problem, provide tools for learning and engagement, and build a community of support for solutions moving forward.

- Coalition of Environmental Orgs Releases Policy Platform for “Zombie Mines” Reclamation Work

- West Virginians could get stuck with cleaning up the coal industry’s mess

- The future environmental and health impacts of coal

- Poverty and Mortality Disparities in Central Appalachia: Mountaintop Mining and Environmental Justice Mountaintop Mining and Environmental Justice

- Modern Coal Mines’ Cleanup Has Big Unbudgeted Costs, Group Says

- Coal Mine Bonding, Bankruptcy, and Unreclaimed Post Law Mines

Abandoned vs. Modern-Era Mines

What’s the Difference and Why Does it Matter

In 1977, Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). SMCRA covers all coal mines as well as surface mining operations, coal prep and processing facilities, waste piles, and coal-loading facilities that are near a mine site. The legislation established permitting and bonding requirements, performance standards, and state programs for inspection, enforcement, and reclamation. Before SMCRA, coal mining in the United States was unregulated for more than 200 years.

Coal mining that took place before SMCRA is referred to as “pre-law” mining and the sites are classified as Abandoned Mines Lands (AML). Coal mining that took place after 1977 is referred to as “modern-era” mining. While both AML and modern-era mine sites can have significant negative environmental impacts, these impacts are managed under different regulatory and reclamation programs. States are responsible for cleaning up AML sites, using funds provided by the federal government. SMCRA, in contrast, is premised on the requirement that modern-era mine operators completely reclaim mine sites, while also requiring mine operators to set aside reclamation bonds to ensure sufficient money will be available to fully clean up any mines that may be abandoned.

The Alliance for Appalachia, alongside dozens of partner organizations across the country, has been advocating for funding to clean up AML sites for almost a decade. The grassroots-led efforts resulted in the introduction of the RECLAIM Act and ultimately, our advocacy paid off. The newly passed Infrastructure Bill provides $11.3 billion over the next fifteen years to clean up coal mine sites that were abandoned prior to 1977. These funds will go into the “Abandoned Mine Lands (AML)” Program, which was created through SMCRA to address a 40+ year toxic legacy and ensure the burden of reclamation, toxic pollution, and safety hazards didn’t fall on communities. The AML Program has eliminated over 46,000 open mine portals, reclaimed over 1,000 miles of dangerous highwalls, restored water supplies to countless residents, created jobs and economic development opportunities, and protected 7.2 million people nationwide from AML hazards. To learn more about the legacy of Abandoned Mine Lands, see this story map created by Matt Hepler with Appalachian Voices.

Bonding & Bankruptcies

As Coal Declines Bankruptcies Increase

While SMCRA established key regulatory and reclamation standards, it failed to take into account that the coal industry would inevitably decline. For the past decade, coal production has been in decline in Central Appalachia. Now, over half of the coal mined in Central Appalachia comes from companies that have recently gone through bankruptcy. This wave of bankruptcies has produced a lasting concern for Central Appalachian residents: coal companies have taken our mountains, poisoned our waterways, and devastated the health of our communities– from rare cancers to widespread black lung disease among miners. Now, they’re taking their money and running from their responsibilities, leaving taxpayers to cover the costs of cleaning up their mess.

Numerous blogs, webinars, websites, testimonies, and reports document how Central Appalachian bonding mechanisms are under severe stress and undermine health benefits to coal miners and the restoration of waterways and land degraded by coal mining. One worth noting is a story map created by Matt Hepler with Appalachian Voices tracking the Blackjewel Bankruptcies and impacts on the community and environment.

The number of idled and unreclaimed ‘modern era’ coal mines across our region continues to grow, and it’s increasingly clear that many of these mines will become abandoned in the coming years, creating a whole new generation of mines requiring cleanup by regulators. As the demand for coal continues to collapse and companies go bankrupt, the standard bonding mechanisms are currently insufficient to address a systematic widespread collapse of the coal industry and the costs of reclamation.

In April of 2018, The Alliance for Appalachia produced a report detailing regulatory problems with the bonding industry in the Central Appalachian states of Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The report highlights deficiencies in several types of “alternative bonding systems.” Bonding is supposed to be a safeguard so that reclamation will be completed, even if a company can’t perform the reclamation work. Unfortunately, that safeguard is not working as planned.

The current SMCRA statute and regulations provide regulators with considerable flexibility in designing and implementing a bonding program. In addition to full-cost bonding, regulators may employ a variety of other alternatives. These alternatives have been at the root of many bonding program deficiencies, including deficiencies exposed by the recent sector-wide financial difficulties facing the coal industry. They allow mine operators to avoid posting a bond for the full reclamation amount, and thereby pass the risk of default to the regulator and, by extension, the communities who live near the authorized mine.

Repairing the Damage

The Costs of Delaying Reclamation at Modern-Era Mines

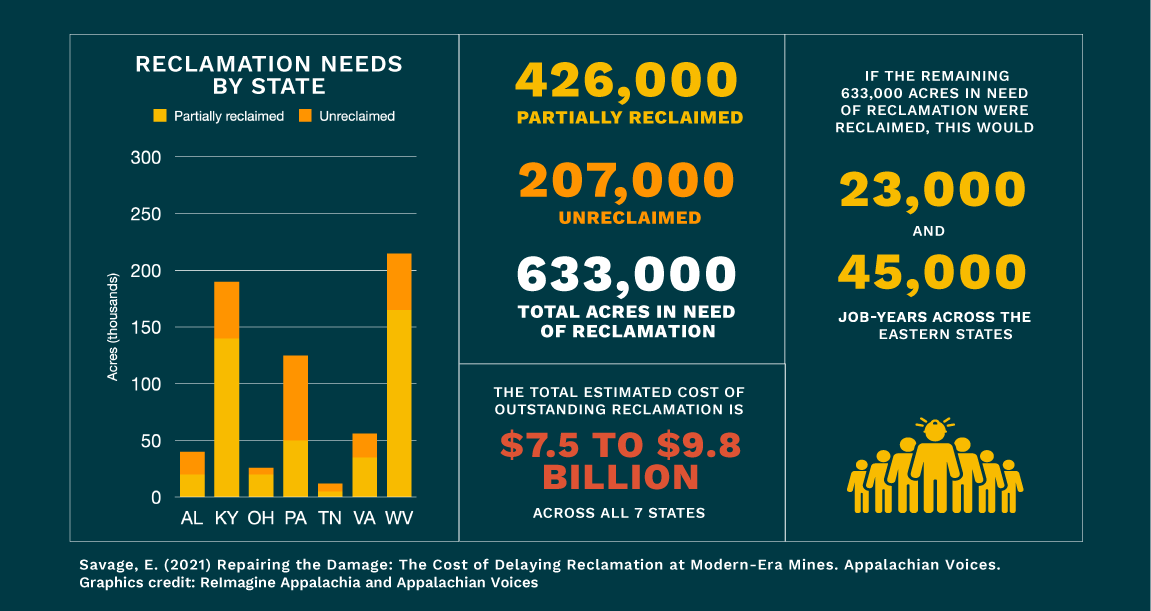

Erin Savage, Senior Program Manager at Appalachian Voices, recently released the first region-wide analysis of Modern-Era Mines to quantify how much reclamation needs to be done and how much this will cost for seven Eastern coal mining states: Alabama, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Watch the press conference to learn more about the research, conclusions, and OSMRE policy recommendations.

Citizen groups should never have to clean up land degradation. – Cindy Rank

We believe that we can achieve environmental justice by building power in communities and connecting people of all backgrounds and identities from geographically and culturally disparate places. In our work, we commit to creating supportive spaces and meeting people where they are in their growth and understanding of complex issues. We lean on people’s personal experiences to tell the stories and perspectives necessary to reach strategic decisions. This project is no different. Most of the following resources were created and shared by members of the Alliance for Appalachia. We invited you to join us in this work so that we can find solutions together.

Get Involved

The Alliance for Appalachia’s Grassroots Water Monitoring & Enforcement Team convenes a space for members to learn from each other’s work around water monitoring, develop enforcement strategies, and share resources between states on issues like tracking and challenging mine permits, engaging in bond release, and teaching residents how to submit complaints and petitions to hold coal corporations accountable.

Alliance member groups and partners also participate in the national RECLAIM working group which grew out of the need for a collaborative working space to push the RECLAIM Act campaign forward with a grassroots focus and now serves as a space to advocate and develop solutions around mine site cleanup and addressing other legacy costs of coal, like miner’s healthcare.

It’s going to take a lot of people and a lot of ideas. Having local folks giving input would lead to land that is more usable in the future. – Tonia Brookman

Become a member group. Learn More.

The Alliance for Appalachia’s Grassroots Water Testing & Enforcement Team hosted a virtual workshop on how to participate in coal mine bond release proceedings- how to monitor for bond releases, request inspections, and participate in the site inspection. This is a great way to add a layer of accountability for sufficient land and water reclamation.

- Whether you’re a GIS professional or are just learning to use Google Earth, you can use this data from a collection of maps compiled by Appalachian Voices.

- The Appalachian Waterwatch website has been created to help local people in Central Appalachia report and track incidents of water pollution.

- https://ace-project.org/ for groups who want to plug into tracking community water testing efforts.

- This government-wide list offers easy access to Energy Communities applying to fund infrastructure, environmental remediation, job creation, and community revitalization efforts.

Advocate for New Policies

Environmental Justice for All Act

This bill aims to address environmental injustice and is the culmination of years of research and community input from environmental justice leaders who represent some of the very communities this bill is meant to support. If passed and enforced properly, it would significantly strengthen environmental protection for communities that face disproportionate pollution burdens. See this factsheet to learn more about key features.

OSMRE Policy Reform

We will have more updates on legislation and Action opportunities in the coming months but in the meantime please check out this recent webinar.